Shi Yangkun

Shi Yangkun (b.1992, Henan) is currently based in Shanghai. He graduated from the documentary photography program at the London College of Communication in 2016. His artistic practice draws upon personal and collective historical experiences, focusing on the visual construction of violence, trauma and memory, and exploring the dynamics of power and perspective during the transitions of modernity in China.

His works were exhibited at the Forschungscampus Dahlem, Berlin (2025); Goethe-Institut Beijing (2025); A4 Art Museum, Chengdu (2025); Stadtmuseum Berlin (2024); Zhejiang Art Museum (2023); Art Museum of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts (2023); and the Peabody Essex Museum (2022). His works are held in public collections at the Peabody Essex Museum, the Alexander Tutsek-Stiftung Foundation, and the Zhejiang Art Museum.

Selected Works

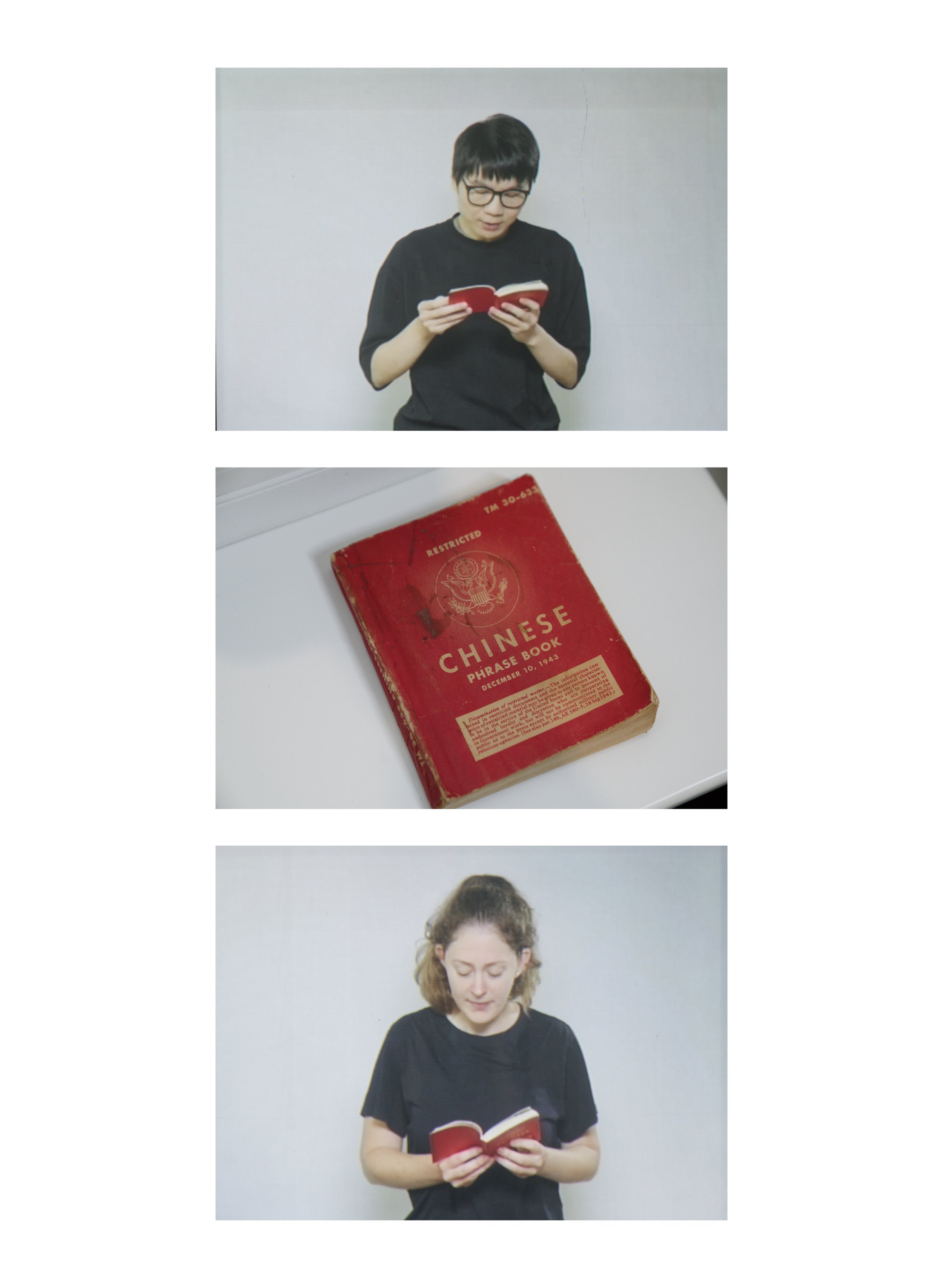

The booklet entitled Chinese Phrase Book (Technical Manual 30-633), published by the War Department (Washington, D.C.) on December 10, 1943, is a US military phrasebook designed for use by American personnel in contact with Chinese speakers during World War II. In 2025, Chinese artist Yangkun Shi and American scholar Lisa Orcutt cooperate to finish this two channel video installation, which Yangkun reads in English and Lisa reads in Chinese with the same word list.

Word List

In the triptych installation, the artist employs Prussian blue to visualize the ocean horizon of Qingdao and the ghostly silhouette of the German Imperial warship SMS Iltis. The vessel was stationed in Qingdao during Germany’s colonial occupation of the Jiaozhou Peninsula. It was later scuttled during the 1914 Siege of Qingdao between Japan and Germany. The work was made during the artist’s residency at the “Decolonial Memory Culture in the City” program in Berlin and exhibited at the Museum Nikolaikirche, Stadtmuseum Berlin in 2024. .

The Mirage

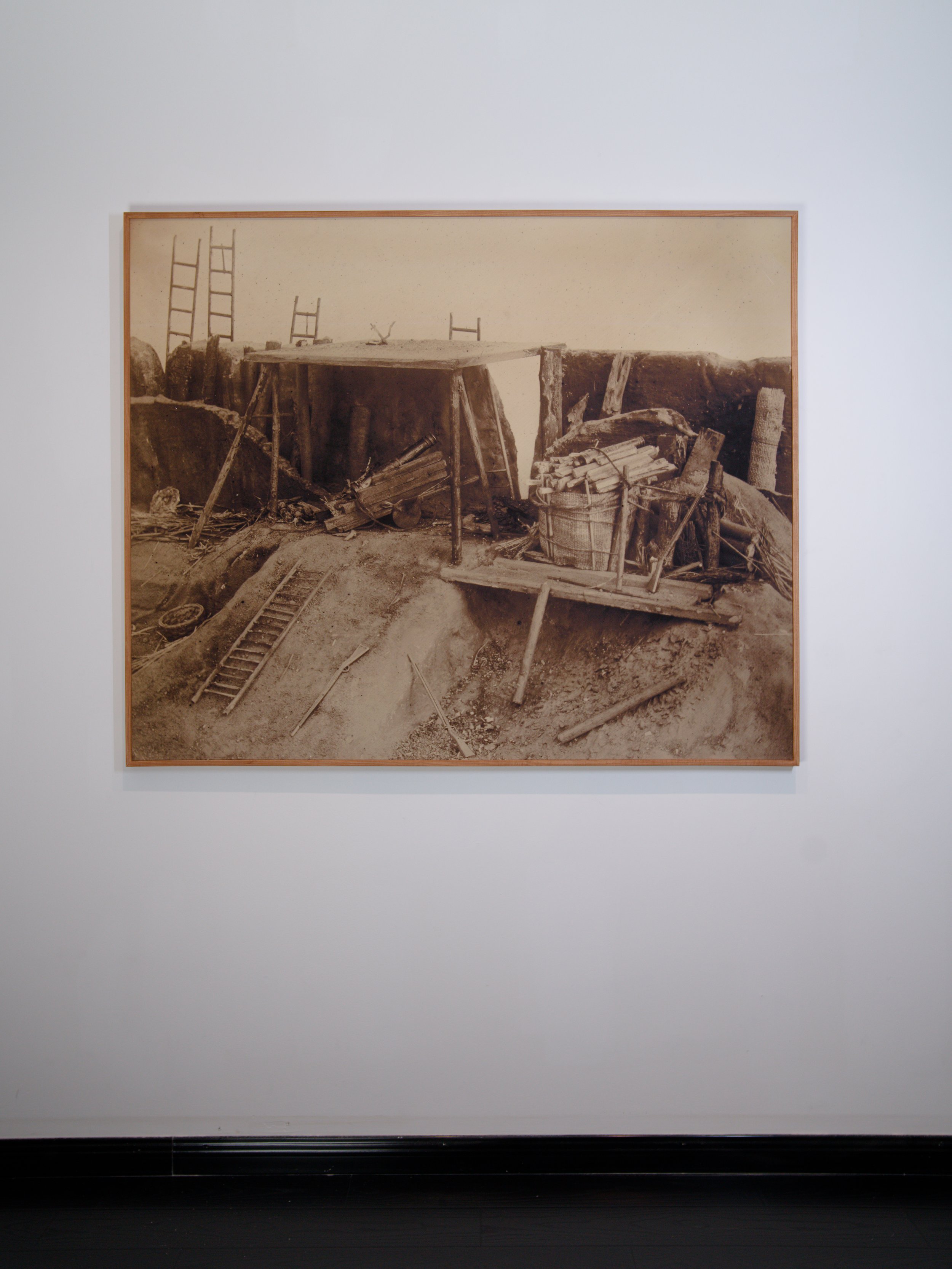

In 1860, during the Second Opium War launched by the British and French allied forces, photographer Felice Beato took the famous photograph After the Capture of the Taku Forts (1860). As scholar Claire Roberts has revealed in the book of Photography and China, Beato rearranged the positions of the corpses to achieve a perfect composition. The artist reconstructs this war scene through staged settings but removed the corpses, leaving behind a ghostly scene. Beato had moved the bodies during the day to achieve his composition. The artist imagines such rationalized violence returning in the silence of nightmares: In unseen places, those who manufacture violent spectacles encounter violent recoiling.

The Nightmare of Felice Beato

In 1843, following the Treaty of Nanking, imposed after Britain’s victory in the First Opium War, Shanghai was forcibly opened to foreign trade and carved into a patchwork of colonial concessions. As the Western Industrial Revolution progressed, driven by the energies of Light, Heat, and Power, by the early 20th century Shanghai had become the most symbolic metropolis of modernity.

Mao Dun had opened his novel Midnight with the description of Shanghai: “On top of the Western-style buildings, an enormous neon advertisement blazed like fire: LIGHT, HEAT, POWER.” In 2025, the artist wrote these three words in an abandoned and unfinished building in Shanghai by using long exposure.Through this work, the artist exposures the violence brought by the desires of capital and the forces of modernity.

LIGHT, HEAT, POWER.

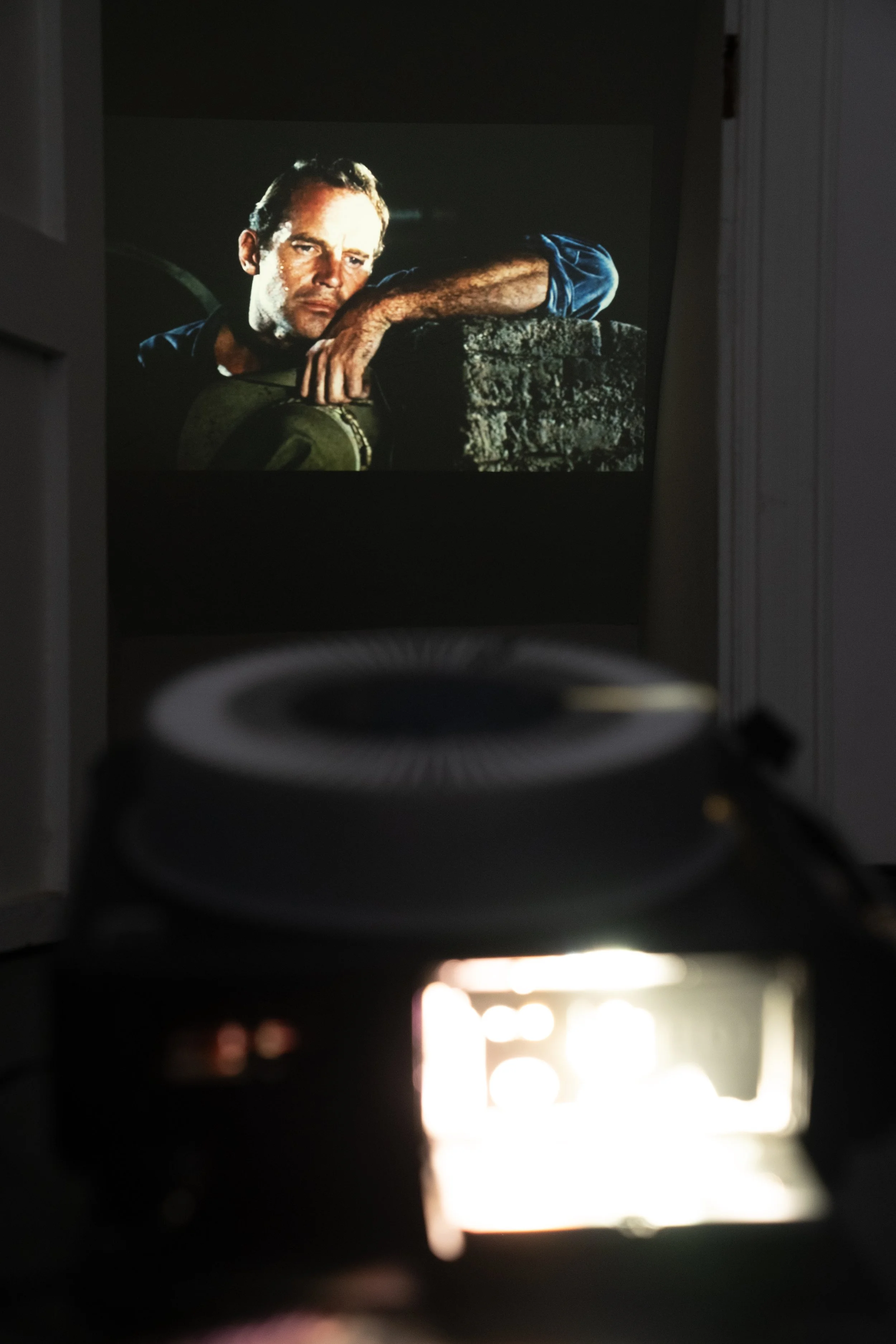

This projector installation draws on footages from three films: Hollywood production 55 Days at Peking (1963), the Hong Kong film Boxer Rebellion (1976), and the Chinese mainland film The Magic Braid (1986). All three depict historical events surrounding the 1900 invasion of Beijing by the Eight-Nation Alliance and the Boxer Rebellion.

The artist extracts ambiguous moments from these films, featuring Boxer fighters, Empress Dowager Cixi, allied soldiers, and street performers etc. Removed from the original context and suspended in a liminal space, these figures invite reflection on the subtle relationships among history, reality and fiction.

Trance

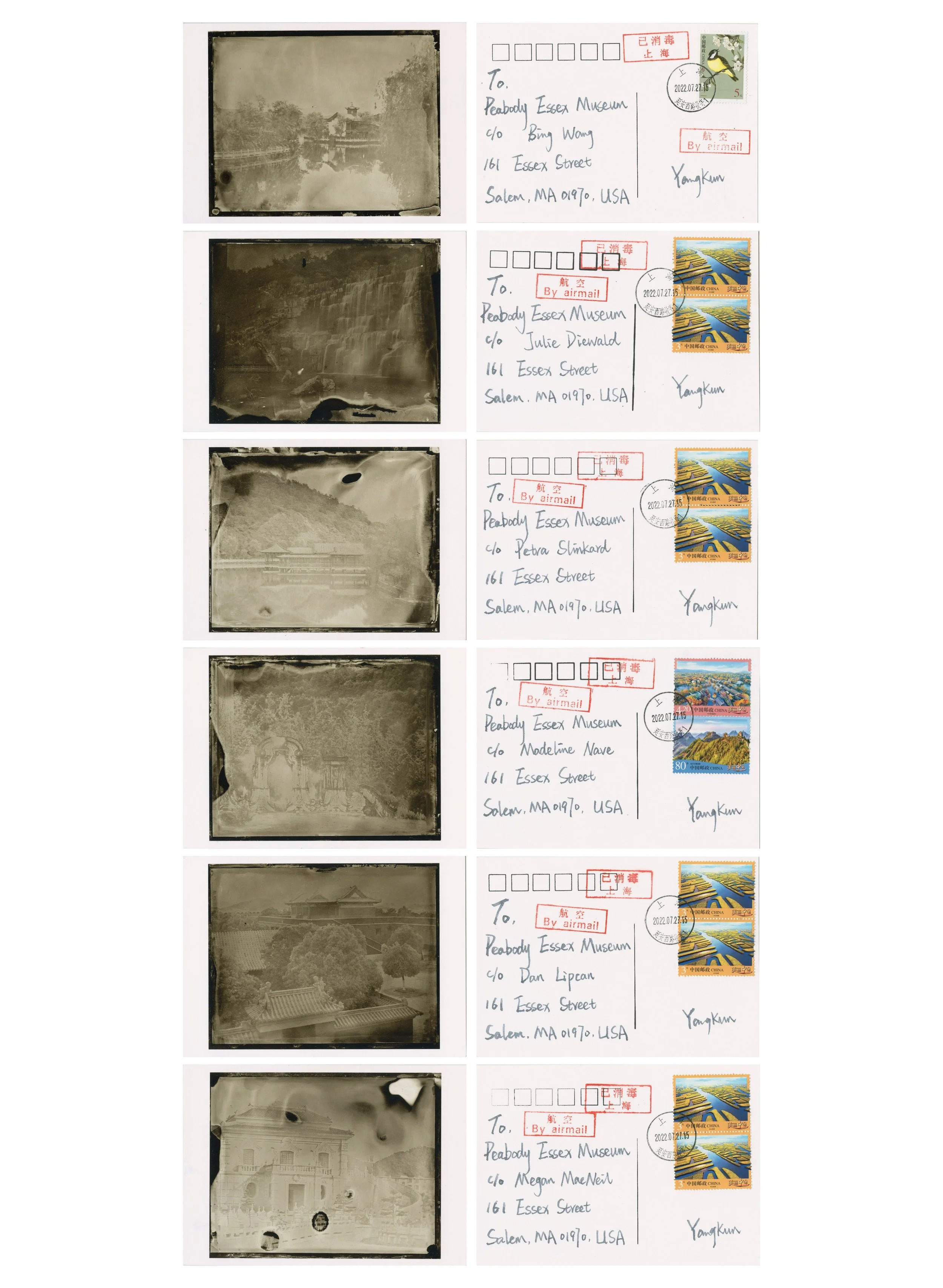

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, British and French troops invaded Beijing, looted Yuanmingyuan, and burned it to the ground. Among the artifacts seized by French forces were the Forty Scenes paintings, which was commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor, as the only surviving visual record of the Chinese sections of the original palace complex. Today, it remains in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Inspired by history, the artist traveled to Hengdian World Studios, one of the largest film sets in the world, to photograph a full-scale replica of Yuanmingyuan, which was built based on the Forty Scenes paintings. He used the collodion glass negatives, a labor-intensive 19th-century technique widely employed by early Western photographers. The images were printed as postcards and physically mailed to the Peabody Essex Museum. These images are surreal and uncanny, prompting us to question how histories are constructed, distorted, and fragmented—particularly as knowledge travels across vast distances and through shifting powers.

Forty Views of Yuanmingyuan

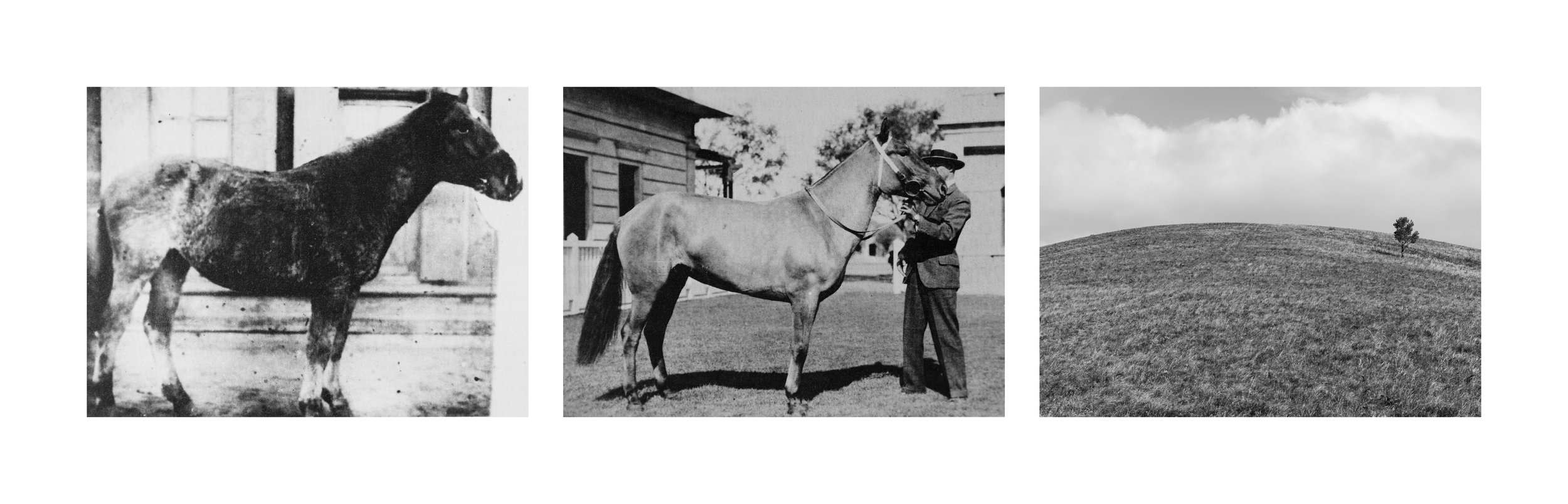

In the late Qing period, after racecourses were established in the foreign concessions of cities such as Shanghai, Tianjin, and Hankou, the primary task was to secure a supply of horses. Initially, this relied on horses imported from Britain or its colonial area, but the long journey made the costs high. Gradually, Mongolian horses became the main source. They were transported from the Mongolian area to Tianjin and then shipped by water to Shanghai, which laid the foundation for British-style horse racing in China.

Diana is the name of a Mongolian horse documented in two photographs around 1927 by Baron Andreas von Delwig. The two photographs document the contrasting appearances of Diana before and after as a racehorse. The artist selected a landscape photograph taken on the grasslands of Inner Mongolia and made it as the third image in the work.